Coastal Immunology

The original short articles on immunology published on this site were written by student teams enrolled in the Immunology BIOL405/L course at Coastal Carolina University.

The Idea. Undergraduate students gain experience by researching reliable scientific literature on immunology, writing articles, and contributing to society by sharing their findings widely.

Due to the nature of this initiative, students choose topics of their interest, which produces distinct collections of articles with a common focus on contemporary, yet diverse themes in immunology. These contents are not intended as medical or professional advice.

PD-1/PD-L1’s Role in Immunotherapy

PD-1/PD-L1’s Role in Immunotherapy

Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Challenges and Perspectives

Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Challenges and Perspectives

Spring 2024

The 2024 compilation includes articles on immunotherapy, how acute myeloid leukemia compromises immunity and challenges therapy, and a discussion on the development of oral vaccines that could democratize vaccination worldwide.

PD-1/PD-L1’s Role in Immunotherapy

Alexei Chesnutwood, Gabriella Caldwell, Crystal Addis, Isabella Schmidt,Tennisyn Parrish

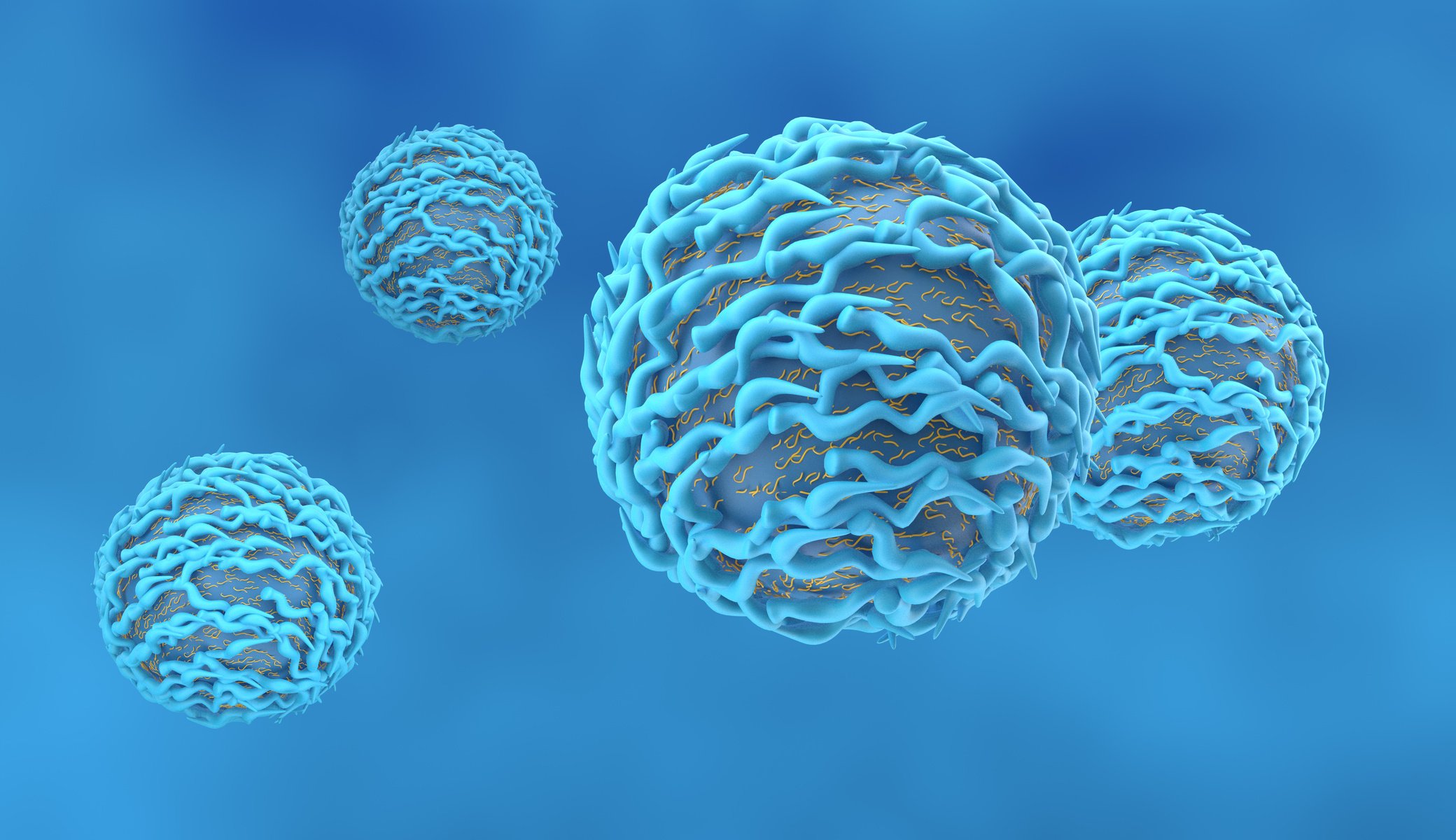

Programmed cell death protein-1(PD-1) is an inhibitory receptorlocated on the surface of T lymphocytes, playing a crucial role in maintaining both central and peripheral tolerance within the immune system. When PD-1 engages with programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1), it initiates the release of inhibitory signals that dampen T-cell activity. This interaction acts as a negative feedback mechanism, resulting in the suppression of T cells and their cytotoxic functions. Such regulatory pathways work to balance the activation and deactivation of T cells, ensuring appropriate immune responses. This precise regulation helps to avoid autoimmune reactions and immune-mediated tissue damage, while still enabling an effective immune response.

Tumor cells can hijack the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, therefore disrupting the balance of the immune response. Upon recognition of an abnormal tumor antigen presented on the major compatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules, T cells secrete interferon gamma (IFN-γ) to boost the efficacy of tumor eradication. The secretion of IFN-γ by CD8+ T cells increase the expression of PD-L1 on tumor and stromal cells. Simultaneously, T cell receptor (TCR) signaling elevates the expression of PD1 on the surface of T cells, which binds to PD-L1 on the tumor cells which induces a negative regulatory effect and dampens the antitumor activity of T cells. This allows the tumor cells to evade destruction and continue proliferation.

Checkpoint inhibitors are a branchof immunotherapy drugs that target the interactions between checkpoint proteins. Checkpoint inhibitors often block the interaction between PD-1 and its ligand PD-L1 preventing the issuance of the deactivation signal and allowing for T cells to remain active and functional, which leads to better recognition and attack of cancer cells.

Melanoma, a cancer known for its immunogenicity, was the first cancer type to be effectively treated via PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. PD-L1, found on the surface of melanoma tumor cells, binds with the PD-1 receptor, dampening T-cells' ability to recognize and attack melanoma cells. Two monoclonal antibodies, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, are approved for melanoma treatment. Complete immunoglobulin G (IgGs) are preferred for the treatment of melanomas due to the presence of the crystallizable (Fc) region allowing for the activation of effector functions. Fab and Fab2 immunoglobulin fragments (often used in the therapeutic applications of immunoglobulins) do not contain this region and therefore lack effector functions, which is crucial to the treatment of an aggressive cancer. Melanoma requiresan aggressive immuneresponse, therefore the cytotoxic functions activated by the IgGS are ideal to elicit a strong immune response.

References

(1) Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligandsin tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677-704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. PMID: 18173375; PMCID: PMC10637733.

(2) Patsoukis N, Wang Q, Strauss L, Boussiotis VA. Revisiting the PD-1 pathway.Sci Adv. 2020 Sep 18;6(38):eabd2712. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd2712. PMID:32948597; PMCID: PMC7500922.

(3) Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, Leming PD, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Horn L, Drake CG, Pardoll DM, Chen L, Sharfman WH, Anders RA, Taube JM, McMiller TL, Xu H, Korman AJ, Jure-Kunkel M, Agrawal S, McDonald D, Kollia GD, Gupta A, Wigginton JM, Sznol M. Safety,activity, and immunecorrelates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jun 28;366(26):2443-54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. Epub 2012 Jun 2. PMID: 22658127; PMCID: PMC3544539.

(4) Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, Wolchok JD, Hersey P, Joseph RW, Weber JS, Dronca R, Gangadhar TC, Patnaik A, Zarour H, Joshua AM, Gergich K, Elassaiss-Schaap J, Algazi A, Mateus C, Boasberg P, Tumeh PC, Chmielowski B, Ebbinghaus SW, Li XN, Kang SP, Ribas A. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 11;369(2):134-44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. Epub 2013 Jun 2. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 29;379(22):2185. PMID: 23724846; PMCID: PMC4126516.

(5) Hung AL, Maxwell R, Theodros D, Belcaid Z, Mathios D, Luksik AS, Kim E, Wu A, Xia Y, Garzon-Muvdi T, Jackson C, Ye X, Tyler B, Selby M, Korman A, Barnhart B, Park SM, Youn JI, Chowdhury T, Park CK, Brem H, Pardoll DM, Lim M. TIGIT and PD-1 dual checkpoint blockade enhances antitumor immunity and survival in GBM. Oncoimmunology. 2018 May 24;7(8):e1466769. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1466769. PMID: 30221069; PMCID: PMC6136875.

Advancements In Immunization: Exploring The Rise Of Edible Vaccines

Emma Hofseth, Alexandra Bonner, Hunter Sloan, and Regan Verespie

Abstract: Vaccines revolutionized medicine, allowing a person to become immune to a disease without contracting it. The newest development, edible vaccines show great promise and present practical challenges to overcome. Edible vaccines start with genetically modifying a plant to produce an antigen. Then when a person ingests the plant, the cell wall of the plant cells protects the antigen from breaking down in the stomach. The cell wall is broken down in the digestive tract, the antigen is absorbed, and then interacts with the immune system in a similar way as conventional vaccines, resulting in the person’s immunity to the antigen. Edible vaccines may improve on conventional vaccines by forgoing needles, which lowers the risk of spreading blood-borne pathogens. They are also more cost effective, allowing developing nations to afford them. However, antigen stability and dosage remain to be standardized in edible vaccines.

History of Vaccines: Vaccines have only been used for a short time. Edward Jenner is considered to be the father of vaccines due to his research in 1796 where he attempted to fight against smallpox. In his study, he aimed to create immunity by using the pus of an infected person and introducing it to the skin of an uninfected person. A similar strategy, called “variolation” was used before then in China and, likely, Africa. While this was one of the first studies to further vaccine research, it was not until the early 1900s that vaccines became popular. The development of the diphtheria tetanus pertussis (DTP) vaccinewas one of the first known vaccines recommended for people (1). By the 21st century, the development of vaccines grew exponentially, and people were vaccinated against Measles, Influenza, HPV and Polio (1). Fast forward to today, and vaccines have become a vital aspect of health and safety for many people. The advancements in vaccines have allowed us to grow,learn, and try new ways to counter contagious diseases.

How Vaccines Work: The body has numerous ways to protect itself against foreign cells and diseases. Oftentimes, this results in harsh reactions like fevers, vomiting and diarrhea to eliminate the unwanted virus and bacteria as well as cell damage induced by the pathogen. Early vaccines introduced a small amount of pathogen, often heat-killed, into the body to induce the body to produce pathogen-specific antibodies. More recently, purified parts of the pathogen expressed in the laboratory were used to improve vaccine safety and efficacy. The vaccination mixture is injected into the muscle site (2) where it is absorbed, and the antigen molecules are transported to dendritic cells and carried to the lymphatic system where they activate some T-cells. Without an active infection to combat, the T-cells promote the development of B-cells recognizing the antigen that produce specific antibodies as well as memory B-cells that protect the body from subsequent exposure to the pathogen, often for years (2).

The Rise of Edible Vaccines: Edible vaccines are also commonly known as food vaccines, oral vaccines, subunit vaccines and green vaccines. To generate edible vaccines, a specific gene is introduced into a plant by transformation. Thus, the plant is genetically modified to produce the antigenic protein (3). When the plant is consumed, the antigen gets absorbed in the digestive tract and interacts with the immune system similarly to conventional vaccines to create immunity against disease.

The first successful human trialregarding edible vaccineswas conducted in 1997. Elevenvolunteers were given transgenic potatoes expressing the beta-subunit of the E. coli heat-labile toxin, i.e., the causative agent of E. coli-induced diarrhea, to be ingested raw (4). The National Institute of Health reported that ten of the eleven volunteers developed four times the amount of antibodies against E. coli with no serious adverse reactions after ingesting the transgenic potatoes (3). This trial, however, did not determine any long-term effects, which remain to this date, unknown (3).

How Edible Vaccines Immunize: Edible vaccines make use of bioencapsulation, which means the plant’s cell wall protects the antigen from enzymatic degradation in gastric acids, and intestinal secretions before reaching the intestines (3). In the intestine, the antigens are released from encapsulation, and taken up by the M-cells presenton the Peyer’s patches of the intestinal lining. The M-cells express MHC class II molecules and may present the antigens to activate T-helper cells which assist B-cell antibody production (3). The Peyer’s patches serve as a mucosalimmune effector site where the antigen accumulates before traversing the intestinal epithelium (3). The M-cells transport the antigen across the mucous membrane and activate the B-cells within the lymphoid follicles that, upon antigen stimulation, develop into germinal centers. Activated B-cells migrate from the lymphoid follicles to the mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) and differentiate into IgA-producing plasma cells (3). IgA-type antibodies are secreted into the lumen and neutralize the targeted pathogen (3)

Advancements In Immunization: Exploring The Rise Of Edible Vaccines [Part 2]

Emma Hofseth, Alexandra Bonner, Hunter Sloan, and Regan Verespie

Stable vs. Transient Antigen [CG1] Expression in Plants: ‘Stable genomicintegration’ and ‘transient expression using viral vectors’ have both been used successfully to generate genetically modified plants to express antigens for edible vaccines, each offering distinct advantages and potential applications. Stable integration, the prevalent approach, allows for propagation of the encoded genetic information through asexual plant reproduction, such as cuttings, or sexually, in seeds (3). Stable integration allows for the introduction of multiple genes needed for multicomponent vaccines. Integration can occur within the plant nucleus, facilitated by Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer, or within chloroplasts (3). Conversely, transient expression relies on viralvectors to deliver the genetic material to induceantigen expression through controlled infection (3). While challenging to initiate, transient expression routinely yields high antigen expression levels due to viral replication and gene amplification (3).

Host Plants for Edible Vaccines: Plants used for edible vaccines include common crops such as tobacco, potatoes, tomatoes, bananas, and rice. Tobacco was first used for edible vaccines because of its easy, well-established transformation system. However, tobacco may easily cross-pollinate with other tobacco plants, potentially leading to the unintentional contamination of normal tobacco crops with the transgenic one meant for vaccine production (3). Thus, when choosing host plants for edible vaccines, it is preferred to use one that has a low potential for outcrossing. Potatoes are genetically modified easily and reproduce quickly (6). However, while they may be eaten raw, it is much more common for people to consume them cooked. However, cooking leads to protein damage, denaturing roughly 50% of the antigen, possibly rendering the vaccine ineffective (3). Tomatoes can be genetically manipulated and consumed uncooked in a multitude of ways, such as raw fruit, dried up, or made into a paste. However, they are highly acidic, that may be incompatible with the expression of acid-labile antigens. Another con is that tomatoes have low protein content, that lowers their chance of eliciting a powerful immune response (3). Bananas can be consumed raw and are popular favorites, especially among children, making them an ideal edible vaccine option. Bananas are also inexpensive compared to traditional vaccines: while a traditional vaccine for Hepatitis B (HBV) costs around $125, a banana for an edible HBV vaccine costs $0.02 per dosage. On the other hand, cultivating bananas has several specific requirements (3), plants take 2-3 yearsto mature and the fruits have a short self-life (6).

Rice, another popular staple, does not dissolve in stomach acids, and has developed recombinant technology, making it a highly desirable plant for edible vaccines (3), despite its slow growth and special culturing requirements (6). While there are many more host plant options to explore, these are the widely and more extensively used.

Edible vs. Normal Vaccines: There are many notable differences between edible and conventional vaccines, starting with their administration. Conventional vaccines are injected into the muscle, while edible vaccines are ingested, which makes the experience of receiving an edible vaccine more comfortable (4). Edible vaccines aid people with trypanophobia (a fear of needles)and young children, lower the risk of contamination, and eliminate the dependence on trained medical professionals for administration. However, some issues arise with the use of transgenic plants. Edible vaccine efficacy is dependent on antigen stability. Cooking may denature the protein and render the vaccine ineffective. Microbial infestations could ruin crops of plants for edible vaccines. Clear distinction between the transgenic plants and regular plants meant for consumption must be enacted to avoid misadministration (4). On the other hand, edible vaccines are very cost effective and could democratize access to vaccination. While injectable and edible vaccines have production costs, conventional vaccines require sophisticated purification, specialized handling, and cold chainstorage that are substantially more expensive than edible vaccines. This high price often leaves developing nations unable to afford conventional vaccines (5). Once the transgenic plants are obtained, the costs of buying and growing them are comparatively low, even for the crops with relatively short shelf life, making edible vaccines potentially affordable world-wide (5). Another significant difference between conventional vaccines and edible vaccinesare the knowledge barriers and risks involved in their production. Conventional vaccines are manufactured in specialized laboratories, requiring certified lab technicians, which imposes. a knowledgebarrier. After having acquired the transgenic plants, edible vaccines only require agricultural proficiency (4). Currently, very little research has been done on edible vaccines. Moreover, edible vaccines have not been around long enough to enable us to fully understand their potential side effects (3). Therefore, more large-scale research will be needed before edible vaccines can be adopted widely. One of the outstanding research topics concerns edible vaccine dosage. It has been proven difficult to obtain dosage consistency among distinct fruits, plants, and lots (3). This makesit hard to effectively use edible vaccines, as a low dosage will not confer immunity and a high dosage could lead to vaccine tolerance. Inconsistent dosage is currently the biggest issueedible vaccines are facing.

Advancements In Immunization: Exploring The Rise Of Edible Vaccines [Part 3]

Emma Hofseth, Alexandra Bonner, Hunter Sloan, and Regan Verespie

Conventional vaccines require subsidiary elements, called adjuvants, to stimulate an immune response upon injection, and provide lackluster mucosal immunity (3). On the other hand, edible vaccines do not require adjuvants and stimulate mucosal immunity because the antigens are absorbed in the intestines. Unlike blood immunity, mucosal immunity is important because the most common entry point for pathogens is the mucosal epithelial lining. Having protective mucosal immunity could stop pathogens before even entering the body, while conventional vaccines produce circulating antibodies that effectively intercept pathogens after having breached into the organism (3).

The Potential Impacts of Edible Vaccines: A widespread use of edible vaccines would result in worldwide changes that are hard to predict. Edible vaccines could reduce even further the risk of animal-borne diseases crossing into human populations (4), although modern vaccine production has improved safety substantially. Edible vaccines are distinct from the typical cell-mediated adaptive immunity in conventional vaccines as they confer mucosal immunity. Continued or periodical consumption of the antigen-producing plants would allow to maintain system re-exposure to the antigen in the Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT) through the M-cells (4). Within the GALT's Peyer's patches, antigens are expected to interact with dendritic cells, prompting the production of immunoglobulins and engage memory helper T-cells, potentially indefinitely (4). While this vaccination method is expected to be painless and efficient, some notable concerns remain. Despite centuries of cultivation and artificial selection, plants' developmental unpredictability challenges vaccine dosage standardization (4). Additionally, cooking may degrade proteins and compromise antigen integrity (4). Improper storage can also render edible vaccines vulnerable to microbial spoilage (4). Proper separation between normal and vaccine food crop would be imperative to prevent accidental ingestion and potential vaccine tolerance (4) for which new regulations should be drafted. The workforce should also be updated and retrained for the new jobs created by edible vaccines (e.g., growing and harvesting the transgenic plants).

Edible vaccines offer a revolutionary approach to immunization, that requires no specialized medical training for administration and could be easily transported to remote places. This could break down the barriers to vaccination and enhance its affordability by eliminating the need for costly licensed medical personnel. This streamlined process would enhance vaccine accessibility and foster global health equity. Moreover, the reduced demand for hypodermic syringes resulting from edible vaccines could prompt reallocation of resources toward more specialized medical treatments. While this shift could initially impact needle manufacturers' profits,ongoing innovation in the industry could open new avenues for growth and adaptation for both research and new business models as older practices lose demand and gradually fade out. The transition to edible vaccines may face opposition from companies vested in traditional vaccine production. This economic tensioncould manifest in lobbying efforts or political maneuvers aimed at preserving their market share. Yet, historical precedents, such as the transition away from plastic bags, demonstrate that cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternatives can prevail. Edible vaccines have potentially a strong potential, yet they are currently limited by the problem of inconsistent dosage. If this issue can be resolved, the widespread acceptance of edible vaccines promises to save lives by expanding access to essential healthcare, mitigating biohazardous waste, and conserving resources. This transformation also presents opportunities for medical professionals and corporations to redirect their focus toward other pressing global health challenges.

In conclusion, edible vaccines are similar to conventional vaccines in how they grant a person immunity, and could offer unique advantages over conventional injection vaccines, including easier transportation, storage, and low costs. However, unknowns still need to be resolved through more research, including achieving consistent dosage within every plant and crop, and testing possible side effects and stability in fruit and vegetables. Additionally, many plants are not ingested raw. If the plant is cooked, then the antigenmay be broken down, limiting the effectiveness of the vaccine, or rendering it ineffective (3). Future research will be needed to address these points and make edible vaccines a reality.

References:

(1)The Children’s Hospitalof Philadelphia. (2014,November 20). Developments by year.Children’s Hospitalof Philadelphia.https://www.chop.edu/centers-programs/vaccine-education-center/vaccine-history/develo pments-by-year.

(2) Pollard, A. J., &Bijker, E. M. (2020). A guide to vaccinology: From basic principles to new developments. Nature Reviews Immunology, 21(2), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-00479-7.

(3) Saxena, J., & Rawat, S. (2013).Edible vaccines. Advances in Biotechnology, 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-1554-7_12.

(4) Jan, N., Shafi, F., Hameed, O. bin, Muzaffar, K., Dar, S. M., Majid,I., & GA, N. (2016,June 7). An overview on edible vaccines and immunization. Austin Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences.

https://austinpublishinggroup.com/nutrition-food-sciences/fulltext/ajnfs-v4-id1078.php.

(5) Gunasekaran, B., & Gothandam, K. M. (2020).A review on edible vaccinesand their prospects. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 53(2). https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431x20198749.

(6) Kurup, Vrinda M, and Jaya Thomas. Edible Vaccines: Promisesand Challenges. Molecular Biotechnology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 22 Nov. 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7090473/.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Zhoe Richardson, Markel Dukes, Victoria Robinson

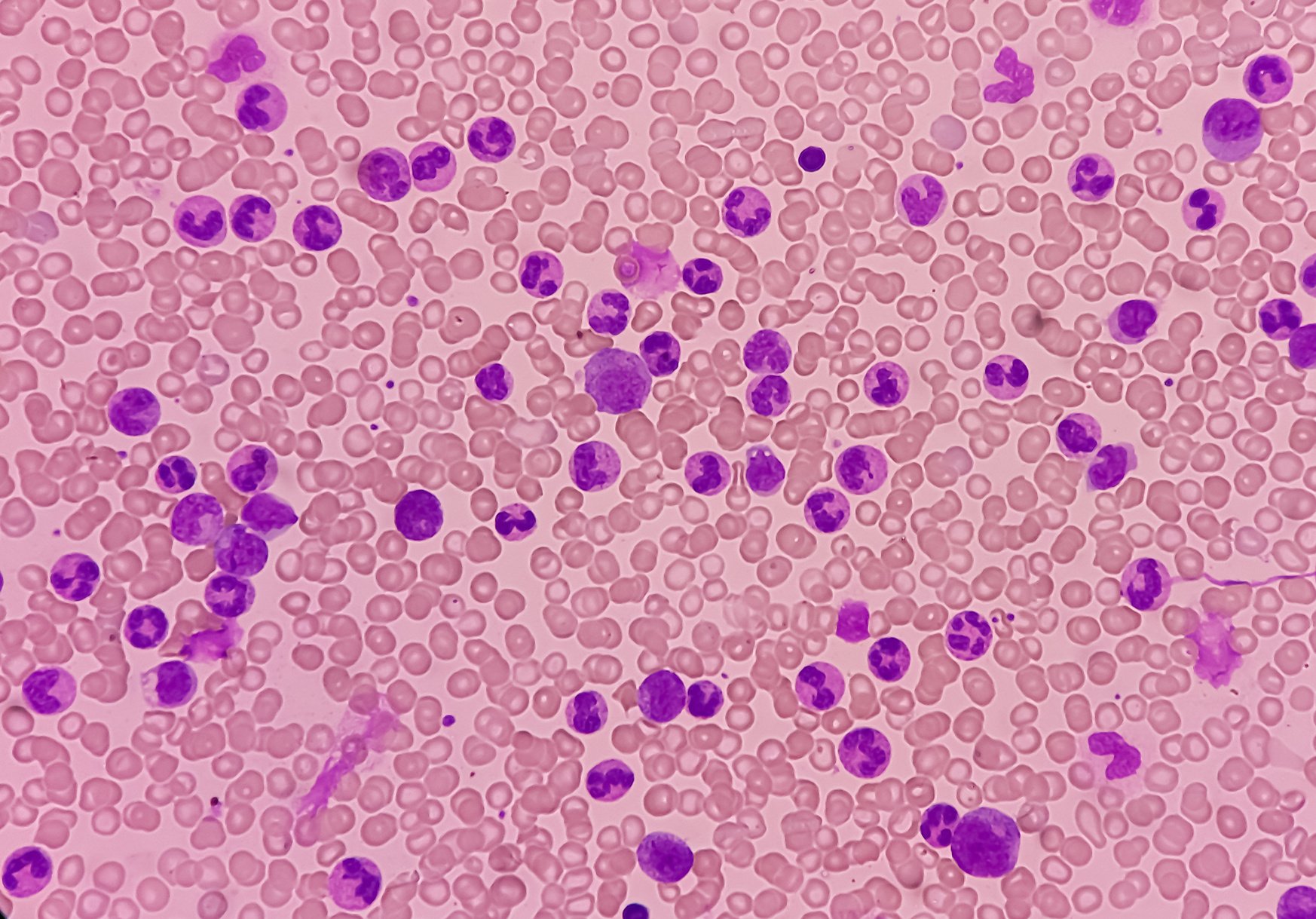

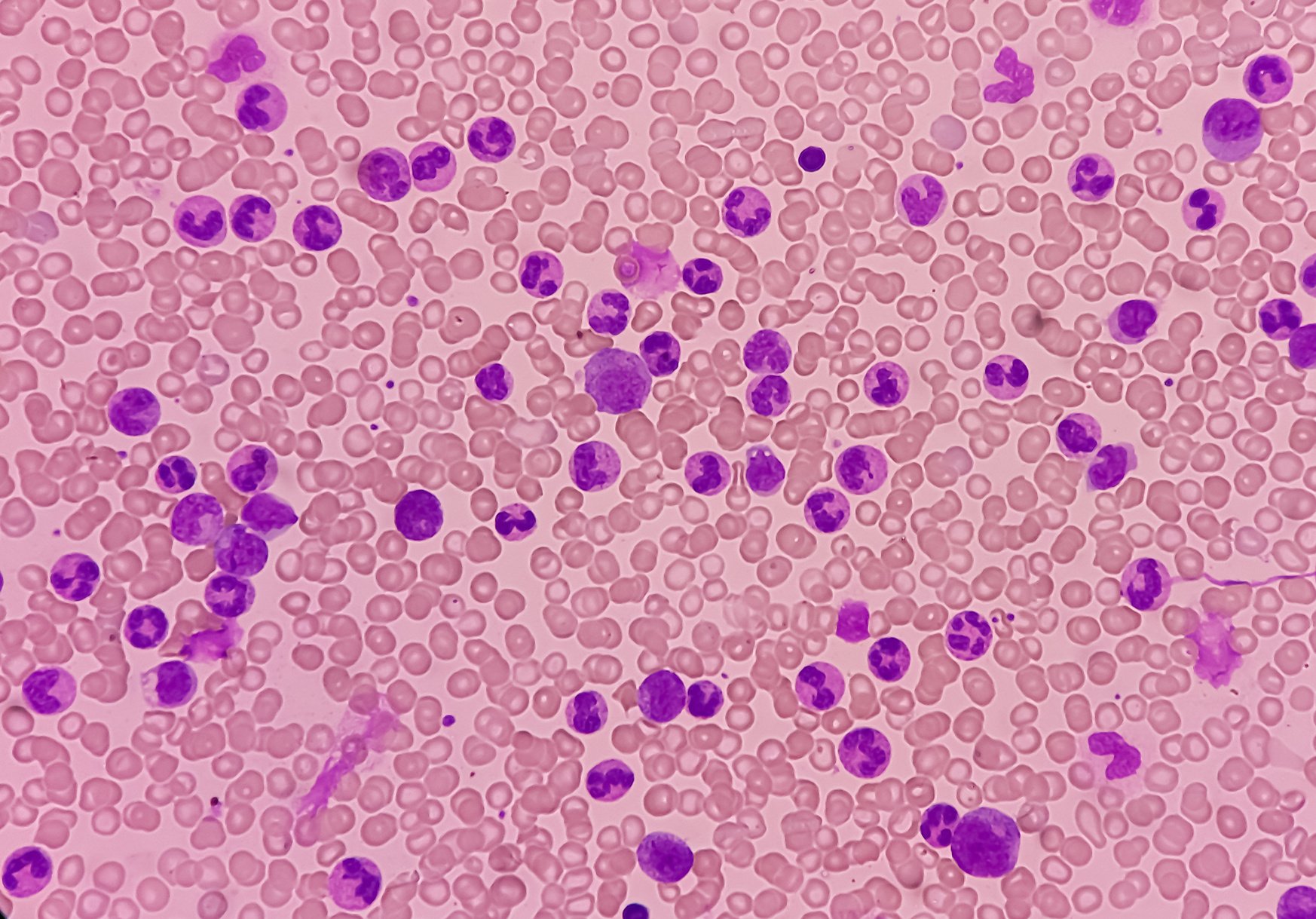

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a type of cancer where immature myeloid cells grow uncontrollably in the bone marrow and blood (Bernson et al. 2017). Although the global rate of leukemia has decreased in the past thirty years, the rates of AML have instead increased by 30% (Dong et al., 2020). Patients treated with chemo/immunotherapy for lymphoid neoplasms during the last two decades face increased risk of developing acute myeloid leukemia (Morton et al. 2023). AML has poor survival rates 24% at five-year, which emphasizes the need to continue research to understand and reduce treatment-related toxicity (Morton et al. 2023). One of the hallmarks of AML is its low number of specific tumor-associated antigens (abbreviated as TSA), which makes it likely to escape immunosurveillance. Indeed, a person’s immunity is the first defense against cancer. Immune cells recognize the TSAs expressed by cancer cells as an abnormal deviation from the individual molecular signature and eliminate them. Cancer occurs only when cancer cells can escape immunosurveillance, for example like in AML, by having little to no TSAs which makes them undetectable. Symptoms of AML can be generic e.g., joint pain, night sweats, pale skin, headaches, and tiredness, which often are unrecognized until AML has reached advanced stages (Williams et al. 2015). AML can either have a high inflammatory component, which makes it a good candidate for immunotherapy, or a low-inflammatory component, which makes it a good candidate for chemotherapy. Chemotherapy can cause severe and fatal reactions such as sepsis and lower the count of white blood cells leading to immunodepression. The lack of TSAs in AML also impairs immunotherapy, that relies on tagging cancer cells with antibodies recognizing features typical of the cancer cells. AML immunotherapy is intensely studied, but initial attempts have shown that to become effective it has to overcome lack of TSAs, tumor heterogeneity and bone marrow complexity. However, some antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) now have FDA approval for use in conjunction with chemotherapy (Tian & Chen, 2022). This ADC, gemtuzumab ozogamicin, targets the CD-33 antigen, which is expressed in 90% of AML patients (O’Hear et al., 2015). Once bound to the AML cells, this drug is internalized releasing the cytotoxic drug that eventually kills the cancerous cells (Tanaka et al. 2009). Venetoclax is an oral therapy used to treat AML, and other leukemias that targets the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 (highly expressed in AML). Inactivation of the BCL-2 “cell survival” signal eventually kills the AML cells. Azacitidine, instead, is a chemotherapy drug that has a dual function. On the one end, it reduces DNA methylation which normalizes gene expression. On the other end, it can be cytotoxic, by being incorporated into nucleic acids and interfering with DNA and protein synthesis (Drugbank). High remission rates were observed from patients who have used Venetoclax and azacitidine (Bernardi et al., 2022).

In the context of cancer, including leukemias and AML, minimal residual disease (MRD) refers to the small number of cancer cells that may remain in the body during or after treatment, even when the patient is in remission. MRD is used to plan therapies appropriately and assess treatment effectiveness, predict the likelihood of relapse and monitor the occurrence of relapse (Bernardi et al., 2022). Monitoring MRD levels allows oncologists to make more informed decisions about treatment strategies, such as whether additional therapy or closer surveillance is needed to prevent relapse. MRD testing involves sensitive laboratory techniques, such as flow cytometry or polymerase chain reaction (PCR), to identify and quantify residual cancer cells at levels lower than what can be detected by standard tests. In AML, achieving MRD negativity, no detectable residual disease, is often associated with better long-term outcomes.

Low-intensity treatment for AML is an approach that typically involves less aggressive chemotherapy regimens. It may be suitable for older adults or those who are not fit enough to tolerate intensive treatments due to other health conditions. Low-intensity treatments aim to control the disease and manage symptoms while preserving quality of life. High-intensity AML treatment involves aggressive chemotherapy regimens that aim to achieve remission, where the leukemia cells are undetectable in both the bone marrow and blood. This often involves higher doses of chemotherapy drugs, sometimes combined with other treatments like stem cell transplantation. High-intensity treatment is usually considered for younger, healthier patients who can tolerate the intense therapy and have a better chance of achieving long-term remission.

AML also changes how certain cells, known as multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), in the bone marrow function, making it harder for these cells to support normal blood cell production. In one study, researchers aimed to understand how MSCs play a role in helping leukemia cells grow and how they contribute to normal blood cell production (Sadovskaya et al. 2023). The researchers studied the secretions from the bone marrow cells of AML patients at the onset of AML and during recovery and compared to that of healthy donors.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives [Part 2]

They found that proteins related to bone formation, transport, and immune response were reduced in AML patients differed from those in healthy donors (Sadovskaya et al. 2023). Even after remission, some proteins responsible for cell adhesion, immune response, and other functions were still lower in AML patients compared to healthy donors (Sadovskaya et al. 2023). This shows that AML causes long-lasting, possibly permanent changes in the secretome of the bone marrow cells, even after treatment, affecting their functions (Sadovskaya et al. 2023). AML also involves changes to gene expression due to abnormal DNA methylation patterns. These abnormalities are more common in AML compared to other cancers (Sandoval et al. 2019). Indeed, mutations in the DNMT3A gene, encoding a DNA methylase, are found in 22% of AML patients. These mutations can lead to either too much or too little methylation and understanding these mutations may help to improve our knowledge of how abnormal DNMT3A activity impacts AML patients and develop targeted treatments (Sandoval et al. 2019).

Overall, AML is a type of cancer with increasing global incidence that has been classified as a health concern (Dong et al., 2020). Ongoing research is needed to devise effective treatment plans. AML can be overcome by replenishing healthy T cells, which occurs in the thymus through a process that transforms immature thymocytes into mature T cells through specific selection processes and maintaining a well-regulated immune system. Early recognition of AML symptoms and regular cancer screenings are important for timely diagnosis and treatment. Monocytes play a significant role in the immune response against AML, and more research is needed to figure out how to use them. Some antibody-drug conjugates show promise for immunotherapies in clinical trials. AML also affects the function of multipotent MSCs in the bone marrow, leading to long-lasting changes in their secretome and gene expression. Understanding how these changes occur, and their combined effects can aid in the development of effective targeted treatments for AML.

References:

Bernardi, Massimo, Felicetto Ferrara, Matteo Giovanni Carrabba, Sara Mastaglio, Francesca Lorentino, Luca Vago, and Fabio Ciceri. “MRD in Venetoclax-Based Treatment for AML: Does It Really Matter?” Frontiers in Oncology 12 (July 18, 2022): 890871. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.890871.

Bernson, E, A Hallner, F E Sander, O Wilsson, O Werlenius, A Rydström, R Kiffin, et al. “Impact of Killer-Immunoglobulin-like Receptor and Human Leukocyte Antigen Genotypes on the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Acute Myeloid Leukemia.” Leukemia 31, no. 12 (December 2017): 2552–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2017.151.

Dong, Ying, Oumin Shi, Quanxiang Zeng, Xiaoqin Lu, Wei Wang, Yong Li, and Qi Wang. “Leukemia Incidence Trends at the Global, Regional, and National Level between 1990 and 2017.” Experimental Hematology & Oncology 9 (2020): 14.

Morton, Lindsay M., Rochelle E. Curtis, Martha S. Linet, Sara J. Schonfeld, Pragati G. Advani, Nicole H. Dalal, Elizabeth C. Sasse, and Graça M. Dores. “Trends in Risk for Therapy-Related Myelodysplastic Syndrome/Acute Myeloid Leukemia after Initial Chemo/Immunotherapy for Common and Rare Lymphoid Neoplasms, 2000-2018.” EClinicalMedicine 61 (July 2023): 102060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102060.

O’Hear, Carol, Joshua F. Heiber, Ingo Schubert, Georg Fey, and Terrence L. Geiger. “Anti-CD33 Chimeric Antigen Receptor Targeting of Acute Myeloid Leukemia.” Haematologica 100, no. 3 (March 2015): 336–44. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2014.112748.

Sadovskaya, Aleksandra, Nataliya Petinati, Nina Drize, Igor Smirnov, Olga Pobeguts, Georgiy Arapidi, Maria Lagarkova, et al. “Acute Myeloid Leukemia Causes Serious and Partially Irreversible Changes in Secretomes of Bone Marrow Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 10 (May 18, 2023): 8953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24108953.

Sandoval, Jonathan E., Yung-Hsin Huang, Abigail Muise, Margaret A. Goodell, and Norbert O. Reich. “Mutations in the DNMT3A DNA Methyltransferase in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients Cause Both Loss and Gain of Function and Differential Regulation by Protein Partners.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry 294, no. 13 (March 29, 2019): 4898–4910. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA118.006795.

Tanaka, Masaru, Yasuhiko Kano, Miyuki Akutsu, Saburo Tsunoda, Tohru Izumi, Yasuo Yazawa, Shuich Miyawaki, Hiroyuki Mano, and Yusuke Furukawa. “The Cytotoxic Effects of Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin (Mylotarg) in Combination with Conventional Antileukemic Agents by Isobologram Analysis in Vitro.” Anticancer Research 29, no. 11 (November 2009): 4589–96. No Doi.

Tian, Chen, and Zehui Chen. “Immune Therapy: A New Therapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia.” Blood Science (Baltimore, Md.) 5, no. 1 (January 2023): 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/BS9.0000000000000140.

Williams, Loretta A., Araceli Garcia-Gonzalez, Hycienth O. Ahaneku, Jorge E. Cortes, Guillermo Garcia Manero, Hagop M. Kantarjian, Tito R. Mendoza, et al. “A Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Symptoms and Symptom Burden of Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) and Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS).” Blood 126, no. 23 (December 3, 2015): 2094–2094. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V126.23.2094.2094.

An Immunological Look at The Oral Cavity, Specifically Streptococcus salivarius

Emily Andrews, Jay Deloriea, Jessica Miller, Jerry White

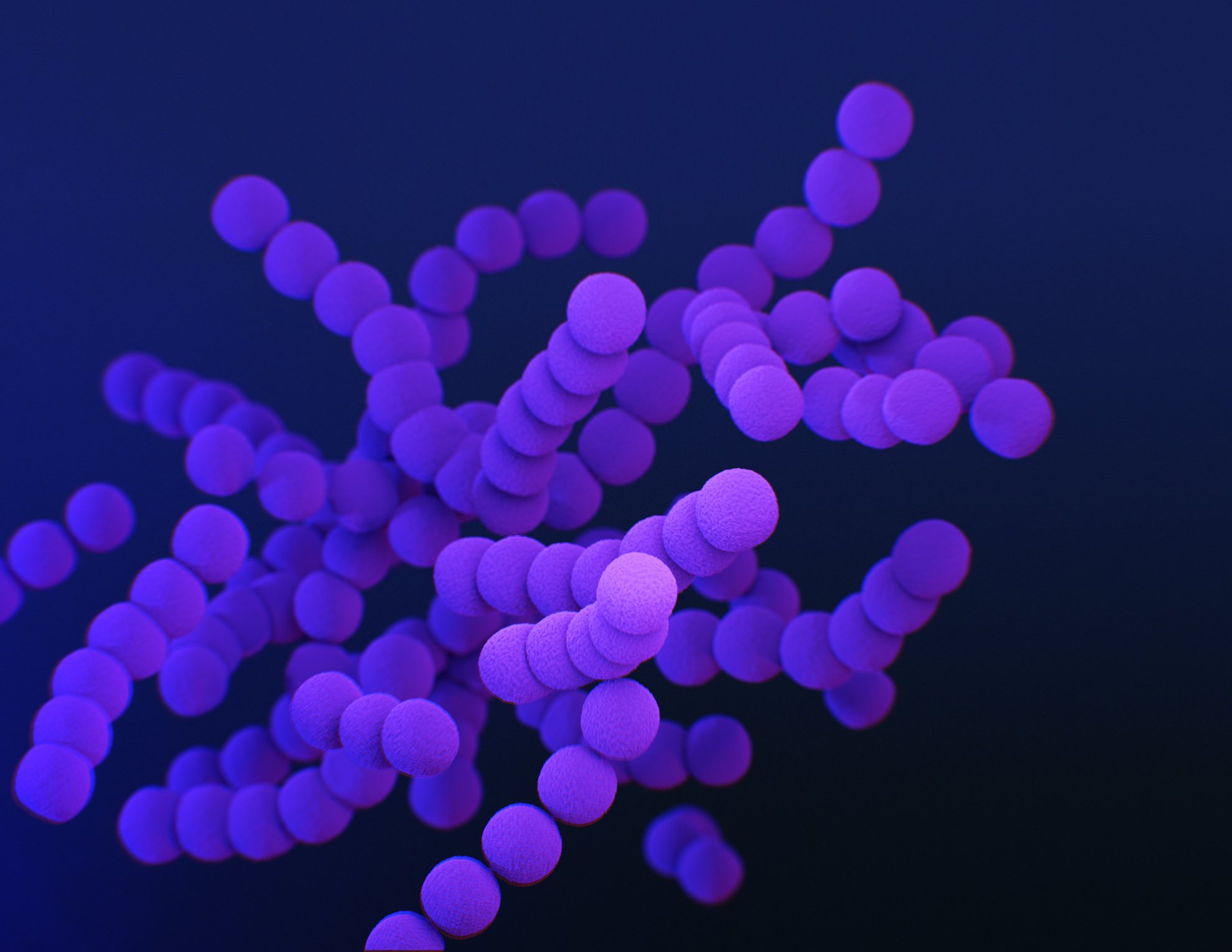

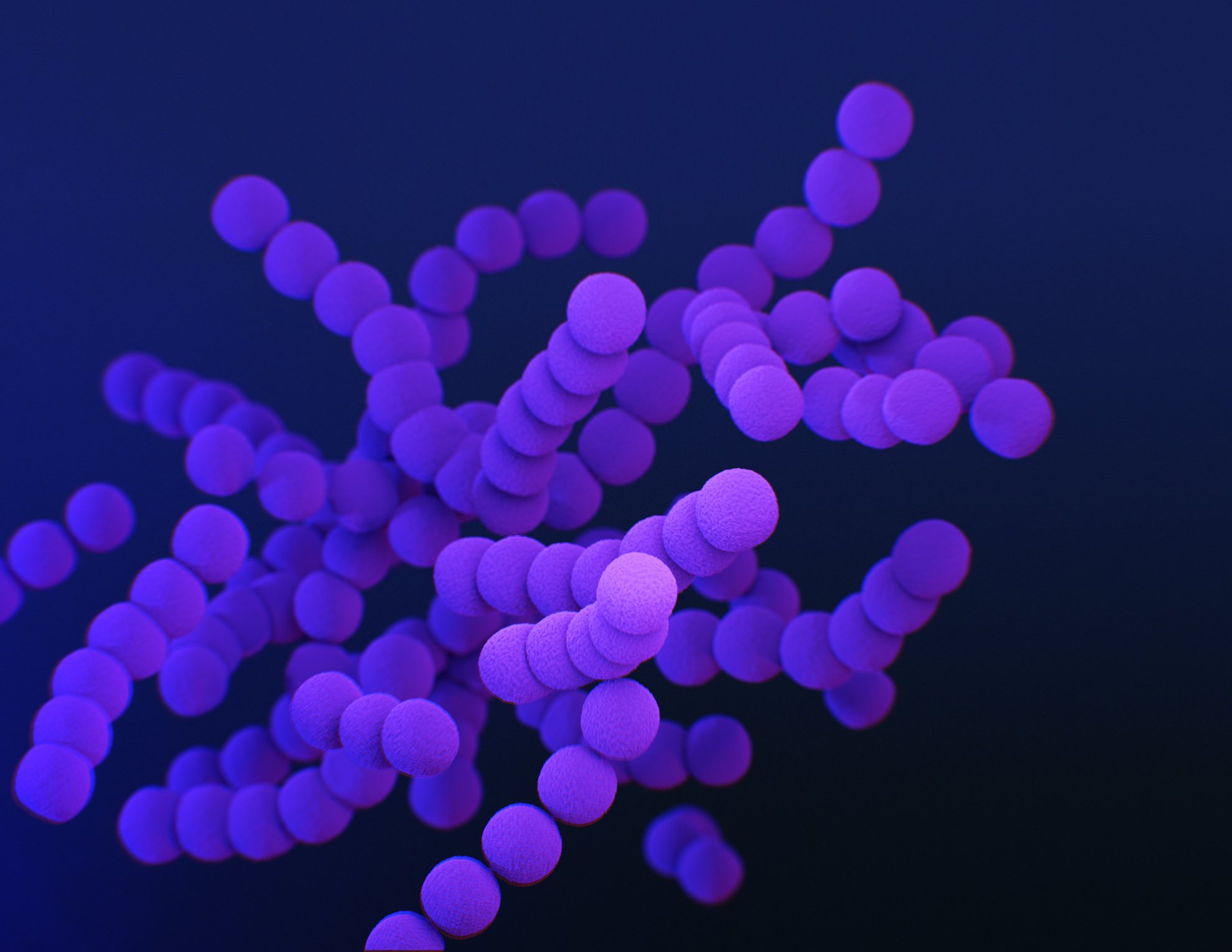

Streptococcus plays a critical role in the oral microbiota and nasopharyngeal epithelia as one of the first microbes to colonize the oral cavity soon after birth (Cosseau, 2008). Researchers discovered that Streptococcus salivarius K12 influenced the host cell cytoskeleton and adhesion (Cosseau, 2008) which allow the bacteria to stick to the tooth surface and spread inside of the oral cavity (Abranches, 2018). The oral cavity provides a suitable environment for bacteria to thrive with small, warm, moist cavities filled with nutrients (Abranches, 2018).

Up to six different Streptococci species have been found inside of the oral cavity, with S. salivarius being one of them (Abranches, 2018). S. salivarius is a Gram positive, facultative anaerobe. If oxygen is present, the microorganism will make ATP through aerobic respiration. However, without oxygen, the organism can survive through fermentation and anaerobic respiration (Abranches, 2018). S. salivarius is known to produce large amounts of alkali metals inside of the oral cavities, which helps to neutralize the acid byproducts produced by other oral Streptococci when metabolizing sugars (Abranches, 2018). Too much acid can break down the enamel on the surface of the teeth providing exposure to opportunistic pathogens and promoting carcinogenesis.

S. salivarius is the predominant colonizer of the oral mucosal surfaces in humans and does not cause infections in healthy individuals (Zupancic et al, 2017). It benefits the host by limiting pathogens from colonizing and helps to influence the normal development of the host cell structure and immune system (Cosseau, 2008). S. salivarius K12 was the first commercially developed probiotic strain due to its abilities to limit pathogens from running rampant in the nasopharynx and oral cavity (Zupancic et al, 2017). Probiotics interact with receptors on the host epithelial cells and activate different pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways to maintain homeostasis (Zupancic et al, 2017). S. salivarius K12 has immunomodulatory properties and actively helps the host defend against pathogens. It can downregulate inflammatory responses by inhibiting the NF-KB pathway and interfere with the synthesis and secretion of interleukin-8 (IL-8), a pro-inflammatory cytokine (Zupancic et al, 2017).

Bacteria can normally coexist with the host, but it may become harmful when host immunity is compromised (Cosseau, 2008). If Streptococci enter the bloodstream, they can cause systemic infections such as endocarditis and pharyngitis (Abranches, 2018). In most cases, the immune system can recognize the Streptococcus when it enters the bloodstream and eliminates them before becoming a life-threatening infection. Unlike beneficial S. salivarius, Streptococcus pyogenes can be rather harmful to humans, causing hemolysis in adults and recurrent pharyngitis and impetigo in children.

It has recently been discovered that S. salivarius K12 inhibits the growth of S. pyogenes and has potential anti-inflammatory properties (Zupancic et al, 2017). One small study found that introducing the K12 S. salivarius probiotic to children that suffer from recurrent episodes of pharyngitis caused by S. pyogenes decreased recurrent infections by upwards of 90% (Zupancic et al, 2017). Although the population size examined in this study was small, other evidence points to S. salivarius K12 having similar protective effects against flares of Periodic Fever with Aphthous stomatitis, Pharyngitis, and Adenitis (PFAPA), a rare and not well studied syndrome that causes a sudden onset of fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis.

PFAPA flares are characterized by a significant increase of circulating chemokines for activated T-lymphocytes, GM-CSF, G-CSF, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 (Francesco, 2016). In this study, S. salivarius oral administration was used to reduce IL-8 release, without changing the IL-1β or TNF-α levels. IL-8 has been implicated in the development of the inflammatory response and, possibly, the pathogenesis of PFAPA due to increased recruitment of neutrophils to the affected area. This study also found that S. salivarius K12 counteracts some of the bacteria implicated in pharyngo-tonsillitis, such as Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae by producing antibiotic salivaricin A2 and salivaricin B that inhibit their growth (Francesco, 2016).

An Immunological Look at The Oral Cavity, Specifically Streptococcus salivarius [Part 2]

Emily Andrews, Jay Deloriea, Jessica Miller, Jerry White

S. salivarius K12 may help maintain homeostasis in the host’s microbiome (Cosseau, 2008). Commensal bacteria such as Streptococcus downregulates the immune response through the critical NF-KB signaling pathways, which can lead to immunosuppression (Cosseau, 2008). The colonization of the S. salivarius K12 strain altered the expression of host genes involved in innate defense pathways, cytoskeletal remodeling, cell development, as well as signaling pathways present in multiple epithelial cells and tissues (Cosseau, 2008). IL-8 secretion and the response to LL37, a peptide mediator of apoptosis, were inhibited as a result of activation of the NF-KB pathway which is a major element in the process of cellular and tissue inflammation (Cosseau, 2008). S. salivarius K12 benefits the host by preventing inflammation and limiting responses to apoptosis inducing peptides (Cosseau, 2008). When S. salivarius is scarce, pro-apoptotic Fas signaling is increased which induces cell death (Cosseau, 2008). Confirming this model, a study in which mice were supplemented with S. salivarius K12 confirmed that S. salivarius K12 reduced cell death and significantly decreased oral microbiota overgrowth (Wang, 2021).

The mechanism behind epithelial tissues tolerating bacteria such as Streptococcus is not completely understood, although altered Toll-like receptor signaling or suppression of inflammatory responses through NF-KB pathway as well as secretion of immunomodulatory IL-10 cytokine have all been implicated in this process (Cosseau, 2008).

Conclusively, the studies on the immunological impacts of S. salivarius are relatively new, and all agree that possible pharmacological applications will require that the bacteria be studied in more depth. Harnessing the immunomodulatory and protective effects of S. salivarius K12 could be beneficial for PFAPA. Similarly, the diverse makeup of the human oral microbiota suggests that plenty of other therapeutic applications could be found. Although preliminary, these studies are promising, and future research is needed to define the therapeutic prospect of modulating oral microorganisms.

Citations:

[1] J. Abranches, L. Zeng, J.K. Kajfasz, S.R. Palmer, B. Chakraborty, Z.T. Wen, V.P. Richards, L.J. Brady, J.A. Lemos, Biology of Oral Streptococci, Microbiol Spectr. 6 (2018) 6.5.11. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0042-2018.

[2] C. Cosseau, D.A. Devine, E. Dullaghan, J.L. Gardy, A. Chikatamarla, S. Gellatly, L.L. Yu, J. Pistolic, R. Falsafi, J. Tagg, R.E. Hancock, The Commensal Streptococcus salivarius K12 Downregulates the Innate Immune Response of Human Epithelial Cells and Promotes Host-Microbe Homeostasis, Infect Immun. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00188-08.

[3] D.P. Francesco, C. Andrea, P. Maria Laura, The Use of Streptococcus salivarius K12 in Attenuating PFAPA Syndrome, a Pilot Study, Altern Integr Med. 05 (2016). https://doi.org/10.4172/2327-5162.1000222.

[4] Y. Wang, J. Li, H. Zhang, X. Zheng, J. Wang, X. Jia, X. Peng, Q. Xie, J. Zou, L. Zheng, J. Li, X. Zhou, X. Xu, Probiotic Streptococcus salivarius K12 Alleviates Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Mice, Front. Immunol. 12 (2021) 684824. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.684824.

[5] K. Zupancic, V. Kriksic, I. Kovacevic, D. Kovacevic, Influence of Oral Probiotic Streptococcus salivarius K12 on Ear and Oral Cavity Health in Humans: Systematic Review, Probiotics & Antimicro. Prot. 9 (2017) 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-017-9261-2

Spring 2022

Following the students’ choice of relevant topics in immunology, the activity wanted to provide an opportunity to research on subjects important to the students, learn to identify valuable information sources, practice scientific communication and contribute to society by providing up-to-date accessible information on timely topics. The 2022 entries cover contemporary themes revolving around the COVID-19 pandemic that has particularly disrupted the learning community and has created anxiety and insecurity about the future. These choice entries represent how science progresses through debate as it navigates the insecurity of novel situations by tackling existing problems and building a body of knowledge that empowers effective solutions. Part of the work of the science educated citizen, is to understand the dynamic nature of this process and being able to identify proper sources of information to apply to their personal and professional realities. Due to the personal nature of the choices, this collection is neither comprehensive, nor to be considered medical advice, but the reasoned reflections of young critical minds worthy of attention.

Novel Immunochromatography of -IgM and IgG Antibodies in COVID Testing

Alexis Brown, Olivia Shirley, Alyssa Simpson, Caitlyn Weinstein

Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2) is a virus causing the COVID-19 severe acute respiratory syndrome. In December 2019, the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in Wuhan, China. Due to its ability to rapidly spread, the outbreak of COVID-19 was soon deemed a pandemic and seen as a global public health threat. The current favored method of diagnosis is quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) that is highly sensitive, but also time-consuming and requires specialized laboratory equipment and technicians. Moreover, RT-qPCR is performed on samples taken from the upper and lower respiratory tracts which increases the chance of exposure to infectious viral droplets. RT-qPCR has been used in clinical settings in the past, however, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, alternative widely applicable diagnostic techniques for the management and prevention of the spread are needed.

Chest computer tomography (CT) scans were studied in China as one such COVID-19 diagnostics. Between 73 and 93% patients with COVID-19 have lung involvement that can be detected by a CT scan before symptoms of pneumonia appear and a positive RT-qPCR test may result. CT scans can distinguish between COVID-19 and other forms of viral pneumonia with a specificity of 24-100%.

Relatively simple and effective, the immunochromatographic (IC) assay; detects the IgM and IgG antibodies found in patients with COVID-19. Recently there has been development of easy-to-use IC assays specific for COVID-19 detection in clinical settings. However, since it is relatively new, the IC assay effectiveness and usefulness are not fully characterized.

IC assays to detect IgM and IgG antibodies were found to identify SARS-CoV-2 successfully and consistently as compared to the qPCR assays. This study (Imai et al., 2020) used 112 patients with confirmed COVID-19 as a positive experimental control. The IC assays were carried out on 139 serum samples from patients at one week, between one and two weeks, and greater than two weeks from COVID-19 onset. IgM antibodies were detected in 60 patients (43.2%) and IgG antibodies were present in 20 (14.4%) of the collected patient samples. IgM antibodies are produced early in the immune response, while IgG antibodies signal a later, mature immune response. Consistent with this characteristic, where IgG antibodies were detected, IgM antibodies were also found in the IC assay. The IgM antibody was detected more prevalently over the course of time, with the greatest detection shown after two weeks. Using immunochromatographic testing of antibodies, was proved to be consistent and reliable in detecting COVID-19. In the control IC assays that were run with specimens from healthy subjects, one false-positive turned out to be a person suffering from Sjogren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis, two auto-immune conditions.

The IC assay was 68% effective in detecting IgM antibodies, in combination with diagnostic chest CT, while no IgG antibodies were found. In the 74 symptomatic patients, 29.7% had IgM and 9.5% had IgG antibodies. The latter patients also displayed IgM. Note, the percentage of symptomatic patients displaying radiographic results consistent with COVID-19 varied over time from disease onset.

Combination of the IC assay with a chest CT allowed for increased diagnostic sensitivity of COVID-19 in symptomatic patients within one week from onset. If confirmed in larger studies, this may imply that when used in combination, IC assay and chest CT may offer an alternative to diagnostic RT-qPCR. However, individually, neither assay was reliable enough to replace it. Potentially limiting use of this new approach in diagnostic, CT scan may not be widely accessible to all patients, and it is only prescribed to symptomatic patients. Because the IC assay measures the antibody response that requires time to raise, it may be most effective when used for epidemiological studies for which ease of performance and limited handling of infectious samples would be assets.

Reference

Imai, K., Tabata, S., Ikeda, M., Noguchi, S., Kitagawa, Y., Matuoka, M., Miyoshi, K., Tarumoto, N., Sakai, J., Ito, T., Maesaki, S., Tamura, K., & Maeda, T. (2020). Clinical evaluation of an immunochromatographic IgM/IgG antibody assay and chest computed tomography for the diagnosis of COVID-19. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology, 128, 104393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104393

Madison Gentilo, Mitchell Dantuono, Madison Ackerly, Brenden Willis, Justin Tremblay

The elderly COVID-19 patient is at higher risk for mortality than young ones. Several changes that occur with aging could be responsible for this fact, including changes in immunological response and declined levels of the hormone melatonin. In addition to being a hormone regulating the sleep-wake cycle, melatonin is a natural antioxidant that can block inflammasomes as well as inhibit programmed cell death. The idea that melatonin may protect from severe COVID-19 came from observations that bats, a reservoir for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, feature higher levels of melatonin than humans. Bats during the nighttime have between 60-500 pg/ml of melatonin. This lowers to 20-90 pg/ml in the daytime. These levels of melatonin are much higher than a typical adult person which has peak melatonin levels of 10-60pg/ml.

COVID-19, like other viral respiratory infections, causes cellular and organ stress from excess release of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that can be increased by the development of positive feedback loops. For example, the SARS-CoV-2 virus specifically induces overexpression of the PLA2G2D protein, which hinders the body's natural antiviral response, allowing for the virus to become more lethal. Reactive oxygen species can be decreased by a molecule with antioxidant capabilities, such as melatonin. High melatonin levels have been linked to reduced inflammation and an increase in other enzymes with antioxidant properties. Melatonin can rebalance several cellular pathways that are compromised in COVID-19. Melatonin inhibits pyroptosis, which is a form of cell death causing inflammation found in COVID-19 (Shneider et. al, 2020). Melatonin has also been shown to down-regulate pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative effects of Nuclear Factor kappa-B (NF-κB) by suppressing its activation in T-cells and delicate tissues. Reinforcing this effect, melatonin also up-regulates NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) which helps to protect delicate tissues. (Zhang et. al, 2020).

SARS-CoV-2 can cause pulmonary fibrosis from lung damage and stress in the alveoli as a complication from mechanical ventilation in severe COVID-19. Animal studies have shown that melatonin can reduce the chances of pulmonary fibrosis by regulating the Hippo/YAP pathway.

Overall, melatonin administration could decrease the number of patients that require mechanical ventilation and decrease the chances of post-COVID complications by simultaneously affecting several cellular pathways adversely affected by the disease. Melatonin is widely available as dietary supplements. While its use in COVID treatment should be under medical supervision, melatonin appears to have the potential to reduce life-threatening symptoms. In this perspective, it is important to consider that melatonin toxicity is desirably negligible, demonstrated by the fact that more than six grams administered per day for over a month did not show any adverse effects (Shneider et. al, 2020).

Contribution Statement: This Blog was evenly worked on by Justin, Madison, Maddy, Mitchell, Brenden

References

Shneider A, Kudriavtsev A., Vakhrusheva A. (2020) Can melatonin reduce the severity of COVID-19 pandemic? International Reviews of Immunology, 39:4, 153-162, DOI: 10.1080/08830185.2020.1756284

Zhang, R., Wang, X., Ni, L., Di, X., Ma, B., Niu, S., Liu, C., & Reiter, R. J. (2020). COVID-19: Melatonin as a potential adjuvant treatment. Life sciences, 250, 117583.

COVID-19 Mortality and Sepsis

Sydney Fox, Brittany Causey, Madison Gwyn, Lauryn Johnson, & Jackie Gould

When pathogens invade the human body, sometimes the host initiates a dysregulated immune response instead of the healthy one needed to eventually clear the infection. That dysregulated and exaggerated response, called sepsis, is a systemic buildup of damaging inflammation in the blood or other tissues, which can lead to organ dysfunction and cell death. Sepsis is life-threatening. When the immune system recognizes a pathogen, small proteins known as cytokines are activated to communicate to and coordinate with other immune cells to act towards the invading pathogen. Although cytokine activation is fundamental when fighting off a microbial infection, excess cytokines, known as a cytokine storm, can hyperactivate the immune system and promote sepsis. Sepsis can also occur when a pathogen is not effectively eliminated, and pro-inflammatory cytokines keep being produced without compensatory anti-inflammatory response. Sepsis is a global health problem that became a central discussion point in 2020 due to the SARS-CoV2 pandemic. In COVID-19, a cytokine storm may contribute to tissue damage that can progress into organ failure. In severe cases, COVID-19 causes sepsis, which in turn leads to ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome) and septic shock. The increased level of pro-inflammatory cytokines in sepsis is like the cytokine storm found in most COVID-19 deaths. Therefore, should the similarity between sepsis and the COVID-19 cytokine storm be confirmed, knowledge of sepsis treatment may potentially inform COVID-19 therapy. Recent studies have shown that while severe COVID-19 cases display cytokine storms, other symptoms such as the pattern of abnormal coagulation, are distinct in COVID-19 and sepsis. Moreover, the SARS-CoV2 virus was found to infect T-cells and cause immunosuppression, the effects of which are long-lasting and overall stronger than the cytokine storm. In contrast, in sepsis cytokine storms are the main issue. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of cytokine storm induction in sepsis and COVID-19 and how it relates to SARS-CoV2-induced lymphopenia may bring a greater understanding of the underlying pathologies and help improve treatment of these conditions.

Olwal, C. O., Nganyewo, N. N., Tapela, K., Djomkam Zune, A. L., Owoicho, O., Bediako, Y., & Duodu, S. (2021). Parallels in Sepsis and COVID-19 Conditions: Implications for Managing Severe COVID-19. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 602848. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.602848

T-Cell Memory to SARS-CoV-2

Maya Aylor, Gina Morello, Candace Howard, An Ly

Infections from the SARS-CoV-2 virus have shown different symptomatology with people presenting asymptomatic cases to the severely ill. In its early stages, SARS-CoV-2 affected more of the elderly than the young population. Although it was assumed that age was directly correlated to disease severity and lack of immune memory, deeper analysis did not show any significant differences in T-cell memory of the elders after infection of SARS-CoV-2. Thus, T-cells from elders and young alike responded to the virus. Early in COVID-19 symptomatology, T-cell immunity appears to be prevalent regardless of disease severity. Additionally, cross-reacting CD4 and CD8 T-cells were found already in blood before the SARS-CoV-2 pathogen was prevalent. which is believed to result from prior encounters with and infections from other coronaviruses. The targets for T-cell reactivity result from genetic mechanisms that use DNA recombination to produce random specificities for each cell and its descendants. As such, reactivity is clonal and both different in each individual and changing over time, as more random specificities are produced. After encountering a pathogen that matches a T-cell specificity, the T-cell is stimulated, and a clone is amplified to eliminate the pathogen. Eventually, memory T-cells are left to protect from later encounters with the same, or related, pathogens. The latter phenomenon is called heterologous immunity and may provide cross- protection or sometimes impaired pathogen control. Heterologous memory is linked to immunodominance, which is when only a few or the many antigens, or features, of the pathogen are targeted by an immune response.

The S (spike) protein is an important viral structural protein that can affect the respiratory system. It is the spike that penetrates the host cell to cause infection and COVID-19. Instead, non structural peptides, or NSP, are nonstructural proteins that are responsible for the replication and transcription of the viral genome. T-cells were found to target both S and NSP peptides with specifics and relative proportions different in each patient., Also the S and NPS proteins show patterns of heterologous memory, different recognitions patterns, and distinct cross-reactivity. SARS-CoV2 cross-reactivity due to past encounters with other coronaviruses in subjects who havenever been infected with SARS-CoV2 may provide some degree of protection in acute infections. In persistent and/or chronic infections, such as those from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as well as COVID-19, T-cell populations may become exhausted due to constant chemical signals and overstimulation. In the case of T-cell exhaustion, inflammation can last many weeks and after disease onset T-cell function is altered, although not completely obliterated.

Among recovered COVID-19 patients, those with mild disease developed detectable T-cell immunity. Compared to the responses in severe COVID-19 cases, there were some different peculiarities. The naïve T cell pool became smaller in older people, which could negatively impact responses to novel pathogens. T-cell memory is also tied to immune response in that for classical memory to develop, the infectious agent must be cleared. When this does not happen, during severe infections, responding T-cells may slow down due to specific cytokine signals and continued TCR stimulation. Severe COVID-19 does not seem to completely eliminate T-cellresponses, but to depress them. It is still unclear whether defects in T-cell response contribute to or are a consequence of the progression to severe COVID-19. The answer to this question will have an impact on our understanding of the the COVID-19 progression and eventual generation of T-cell memory in COVID-19 survivors, which are necessary for effective disease management.

Reference

Jarjour NN, Masopust D, Jameson SC. T Cell Memory: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 2021 Jan 12;54(1):14-18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.12.009. Epub 2020 Dec 19. PMID: 33406391; PMCID: PMC7749639.

T & B Cell Responses After SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Kimmy Weaver, Chesney Price, Ryan Thomas, Logan Stump

While the entire globe has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, new understanding of the SARS-CoV-2 infection has led to the finding of pre-existing immunity to coronaviruses. Figuring out how this immunity works may unlock new ways to protect against COVID-19. The SARS-CoV-2 that led to the pandemic is not the first coronavirus, but it is part of a large viral family among which several viruses cause common colds. Certain elements, like the spike protein, are very similar among related coronaviruses. Inseveral individuals, previous encounters with other coronavirus family members have left immunological memory able to target the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Immunological memory, in these cases, appears to be due to T-cells.

In this study, blood and plasma samples were taken from 28 recovered COVID-19 patients as well as 42 individuals who had never been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and plasmacells were isolated and cryopreserved for various assays used in this study.An enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to detect SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies against the spike or nucleoprotein. To measure antigen-specific memory B cells in the PBMCs, a SARS-CoV-2 specific enzyme linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay was conducted. The PBMCs were stimulated using a potent antiviral drug, R848, and IL-2, an immune signaling cytokine. Antigen-specific memory B-cells were spotted on plates coated with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and nucleoprotein or several classes of generic anti-human antibodies such as IgGs,IgAs, and IgMs. Memory B- cells recognizing the viral proteins would be stimulated to produce antibodies to be detected via fluorescent probes.

To determine the immune memory in COVID-19 patients, collected samples from the 28 patients that hadrecovered from mild cases of COVID-19 were compared to those from 42 healthy donors. In the cohort examined, all patients showed elevated IgG response to SARS-CoV-2, whereas unexposed individuals showed no reaction tospike proteins. Therefore, they had not developed IgG antibodies due to no exposure to the virus causing COVID-19. In contrast, nucleoprotein-reactive IgG antibodies were found in 15 of the 42 unexposed subjects and the titer was elevated in the recovered mild COVID-19 donors, as compared with the unexposed donors with no IgGs. However, this IgG reactivity was due to the immunological memory to alpha and beta coronaviruses causing the common cold. Conversely, recovered COVID-19 patients displayed higher reactivity to the specific HCoV-OC43 variant.Therefore, exposure to several coronaviruses may elicit antibodies able to recognize several members of the coronavirus family that may persist after the initial infection is resolved. T-cells are an important component of the immune response to COVID-19 that may hold the key tounderstand the immune memory found in mild COVID-19 patients that were found in areas with high rates of infection but low rates of fatality. Furthermore, CD4+ T cell reactivity was examined between unexposed and recovered COVID-19 donors in order to differentiate between COVID-19 specific CD4+ T cells through a TCR dependent activation assay.

Seven out of 32 individuals showed marginal frequency of CD4+ T cells recognizing the spike protein. In contrast, recovered COVID-19 patients had a robust SARS-CoV-2 specific CD4+ T cell response. Both unexposed and COVID-19 recovered donors responded to the viral peptide pool and superantigen demonstrating the observeddifference was not due to the inability to mount a response to the SARS-CoV2 virus. Similar responses were found in patients regardless of how long they had recovered from COVID-19. CD8+ T cell counts for SARS-CoV-2 specific cells were compared between recovered patients and unexposed COVID-19 donors.Unexposed and recovered COVID-19 donors consistently responded more readily to the SEB superantigen over the DMSO control. Overall, there was little Spike-specific CD4+ T cell reactivity in unexposed donors but high response in recovered COVID-19 donors. As recovered COVID-19 donors showed great amounts of spike-specific T cells, this led to the examination of B cells. Compared to nucleoprotein assays, the spike-specific IgG assay was six-fold higher than controlsas. IgM-secreting cells were significantly higher in recovered versus unexposed donors. Plasma cells that secrete IgAs were rare in COVID-19 recovered patients, but nucleoprotein-specific IgAs were found in 13 out of 18 donors. These results indicate that there are many Spike-specific IgG secreting B cells within in recovered COVID-19 donors. Despite several months passing after SARS-CoV-2 infection, high concentrations of spike protein andnucleoprotein-specific IgG was observed in participants, demonstrating a continuous antibody response in mild COVID cases and supporting the findings of other studies, which observed no decline in antibodies 4-5 months after diagnosis with COVID-19.

In conclusion, this study found that recovered COVID-19 patients had significant amounts of B-cell andCD4+ T cell specific activity against the SARS-CoV2 spike protein even after five months of recovery. The general population, regardless of COVID-19 status, may have cross-reactions with viral features shared among several other human coronaviruses, such as nucleoproteins, likely due to prior exposure to different coronaviruses. Surprisingly, SARS-CoV-2 specific CD8+ T cells were largely absent, despite having been expected due to their playing a primary role in fighting viral infections. Moreover, how effective memory cells are in countering infection from new viral variants has yet to be determined.

Reference

Ansari A, Arya R, Sachan S, Jha SN, Kalia A, Lall A, Sette A, Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Coshic P, et al. ImmuneMemory in Mild COVID-19 Patients and Unexposed Donors Reveals Persistent T Cell Responses After SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front Immunol (2021) 12:636768. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.636768